The biggest milestones in my design career as a designer have been changes in my attitude toward politics — that constant need to persuade other people, to overcome objections and obstacles, and to build alignment around decisions.

I’ll tidy this process up into a simple timeline:

- When I was first out of school, I resented politics: “I put a lot of effort into building my design judgment and skills, and you’ve hired me to apply them to solving this problem, so get out of my way and let me work.”

- This attitude evolved into a grudging acceptance of politics: “Politics suck but they are unavoidable, so deal with them, so you can do your job.”

- But slowly I began to see that design is largely political: “Politics are an uncomfortable but necessary aspect of design that are best mitigated through human-centered practices.”

- Now I see the most important part of my job as political: “Human-centered design is a massive opportunity to democratize the workplace.”

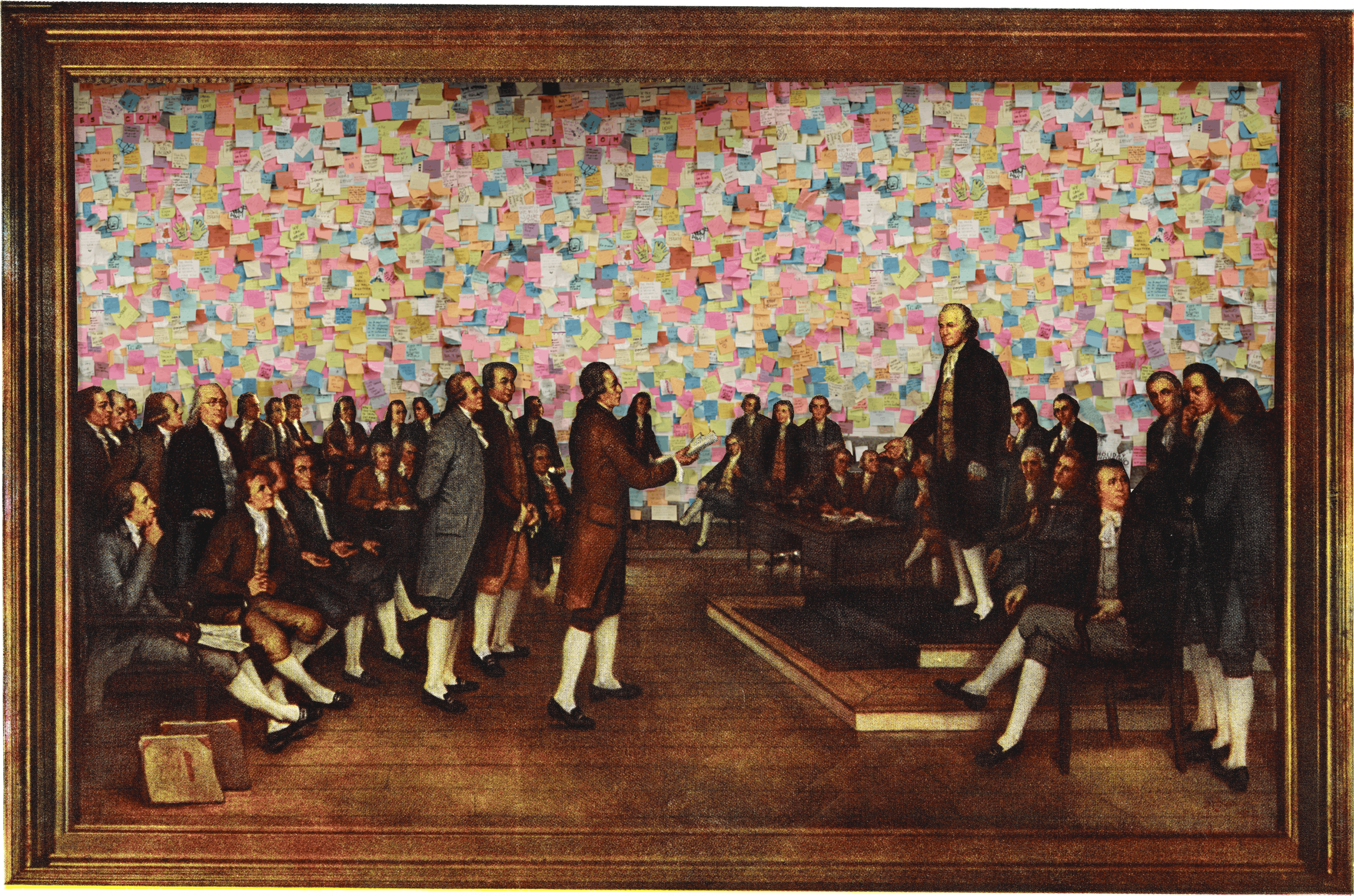

In an effort to work the democratic spirit into how teams work together, I’ve been working on a Design Collaborator’s Bill of Rights. Like all documents of this kind, they anticipate the need to assert rights when they are infringed. As I am usually in the role of team lead, this means I am the most likely to do that infringing. So, this is the document I am giving to my teams, in the case that I step on their toes and fail to lead the way I aspire to. Here is the list as it stands today:

- The right to a brief: every team member has the right to request a clearly framed problem to solve autonomously (as opposed a specification to execute).

- The right to clarity: every team member can request a detailed explanation for any aspect of the project, and keep requesting elucidation until the matter is completely understood.

- The right to argue: every team member can dissent or raise concerns with decisions, and expect to have the concerns addressed.

- The right to propose alternatives: every team member is free to conceive and communicate different approaches to solving problems.

- The right to be heard: every team member’s voice will be actively welcomed in discussions, meaning that opportunities to enter the conversation will be offered and space to communicate without interruption will be protected.

- The right to be fully understood: every team member can expect active listening from teammates, which means they will be heard out and interpreted until full comprehension is accomplished.

- The right to have pre-articulate intuitions: every team member can expect to have pure (pre-articulate) intuitions respected as valid, and to be assisted in giving the intuition explicit, articulate form.

- The right to learn: no team member is expected to have perfect knowledge, judgment, grace or foresight, as long as imperfections are detected, acknowledged and used for learning, growth and improvement.

In the spirit of democracy, I’ll now turn it over to you. How would you change this list? What would you change? What would you add? What would you remove?