As with many people during the early stages of this pandemic, I am experiencing grief for how I used to live. My wife and I bonded early on in our relationship over our shared love for film, food, and travel. I miss the feeling of my feet sticking to the floor of the local art cinema; the warm welcome of our bartender, Jeremy, as we settled into our usual spots at our favorite restaurant; the excitement of visiting a new city (to us) and imagining what it would be like to live there. These places — familiar or foreign — reflect and enhance values core to my identity. Their absence makes it more difficult to be me. The old me.

An important place for me has always been the Public Library. I grew up in Columbia, SC, and was a regular at Story Time and the summer book club. A love of books and writing developed within me, and out of step with my siblings who went into banking and accounting, I got a degree in English Literature. I continue to love not just reading books, but deconstructing them, connecting them, and living with them deeply. After making the leap to service design, I finally got the courage to write one. This life-long journey started thanks to my library and its staff nearly four decades ago.

I’m thinking about libraries today because it’s National Library Week. The theme this year — chosen months ago — happens to be “find your place at the library.” Through the work we do at Harmonic, we know that libraries are more than physical locations with physical materials. They are vibrant engines for creating knowledge, equity, connection, and growth in communities. They create these outcomes in a myriad of ways outside of the four walls of any given branch. This is beyond the obvious (e.g., digital materials), including virtual services, community outreach, and strategic partnerships. The value of these activities is often invisible yet critical to helping communities thrive.

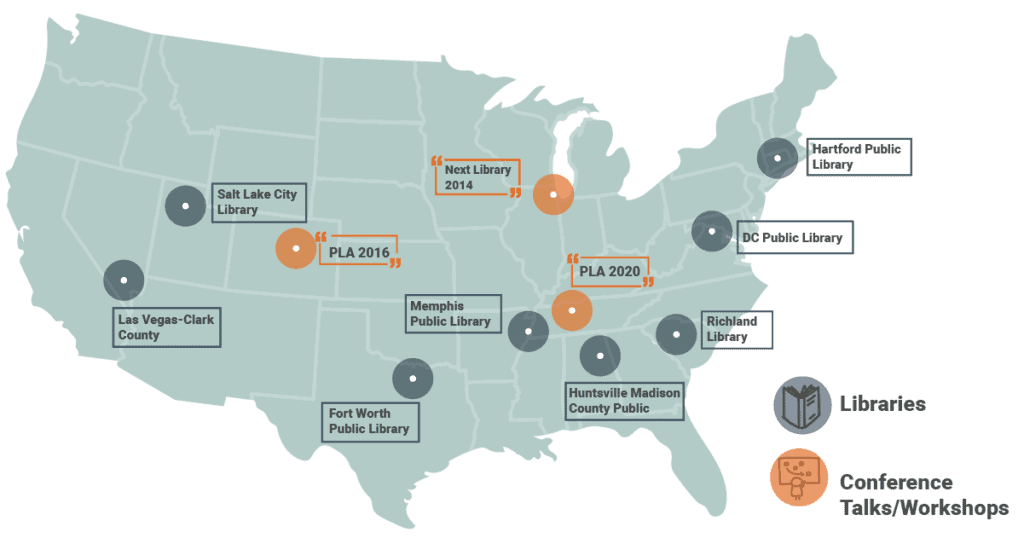

Professionally and personally, I’ve spent a lot of time in (what my friend and colleague Margaret Sullivan calls) Library Land. I’ve had the privilege of working with some of the sharpest, most talented professionals who are shaping what the Public Library will be this century and, in turn, helping transform their communities in an uncertain future. They have invited me to speak, teach, create strategies, design new service models, and have fun with their colleagues and coworkers. In founding Harmonic, I’ve made partnering with libraries (and other mission-based organizations) a continued focus. It’s fulfilling work for our team. It’s a way to align my business with my values.

My father would often ask why I worked with libraries. “Aren’t they obsolete when people have digital books, websites, and Amazon?” This conversation never ended well. (Much like when I tried to explain what I did for a living, a 75-year-old former banker and business owner couldn’t wrap his head around such things). Libraries — like many public institutions — do face challenges as our society continues its evolution from industrialism, products, and person-to-person interactions to a post-industrial society, services, and ubiquitous technically-mediated interactions. But, the primary role of the Public Library remains constant since Andrew Carnegie funded and established the system. As an NPR piece a few years ago put it: “[Thanks to Carnegie] public libraries became instruments of change — not luxuries, but rather necessities, important institutions — as vital to the community as police and fire stations and public schools [emphasis mine].”

What has evolved — and will continue to evolve — is how libraries perform this vital role. As a strategist and designer in Library Land, here are six changes underway that I’ve been championing and collaborating on with my library friends.

Many institutions, including libraries, follow a traditional planning process based on three- to five-year cycles. A lot of effort goes into these plans, including defining many concrete, measurable objectives informed by quantitative community surveys and historical performance metrics, such as material circulation. After being printed, approved, and distributed, these plans then sit on the shelves of government officials, board members, and library directors. See you in five years and repeat.

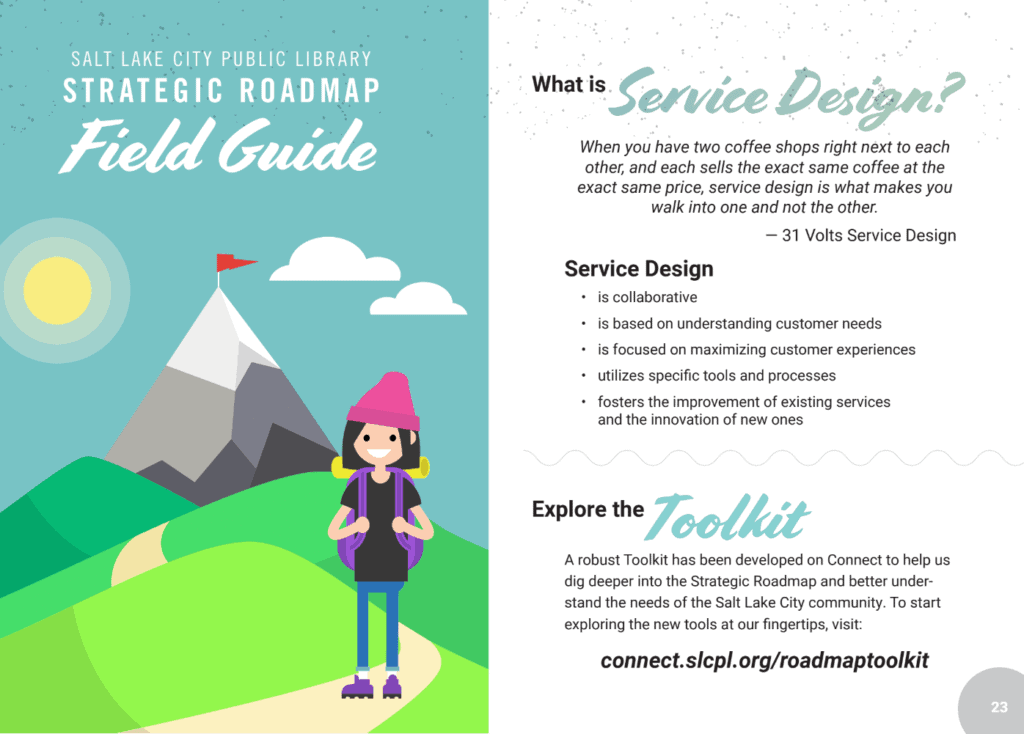

At The City Library in Salt Lake City, UT, this process looks very different. Instead of specific, numeric objectives by the department, there are strategic areas of focus. In place of rigid plans looking years into the future, there are desired outcomes and principles. In lieu of a formal document in a binder that’s referenced irregularly, there is a pocket engaging guide every employee can use on the job to co-create the library’s future.

This approach is based on the philosophy that our world is changing too quickly for set-and-forget strategies and Gantt charts that stretch out beyond the near horizon. In guiding the Salt Lake City team in using service design to develop and activate its strategy, I saw the library staff embrace concepts and approaches that many corporations struggle with. Focusing on outcomes, not solutions. Cross-functional collaboration using a design methodology. Co-creation of strategies with the community. Embracing and engaging the community ecosystem. As a result, The City Library has created a foundation enabling adaptive experimentation in a complex world.

Many young and/or childless adults think of books, DVDs, shelves, and circulation when they hear the word “library.” On average, only 10 percent of a public library’s budget goes to materials, of which a growing percentage are digital books or other digital content (pro tip: if you like film, your local library may have a Criterion Collection account you can use with your library card). As more content becomes digital, many libraries are making shelves lower and opening up floor space for activities other than browsing the collection.

This space is badly needed because libraries aren’t simply places to check out materials while getting advice from amazing, experienced librarians. Libraries are service organizations, and many of those services are critical to creating important outcomes that make communities healthy and resilient. Finding a job. Starting a business. Learning parenting skills. Accessing essential government services. On and on. Most libraries have traditionally provided these services or connected citizens to government agencies or non-profits who do. The difference today is that these services and the outcomes they produce are becoming more explicitly part of the mission of public libraries, leading to a transformation of roles, responsibilities, and the underlying service model.

Seven years ago when I was Managing Director at Adaptive Path, I made it a point to sit across the table from Melanie Huggins at the speaker dinner for our Service Experience Conference. Why? For one, she had just given a wonderful talk about leading a customer experience transformation at Richland Library. Which was exciting because Richland Library is in Columbia, SC, and that’s my hometown. I wanted just to say “hi,” but that first conversation led to a fulfilling collaboration and my express ticket to Library Land.

Melanie invited me to collaborate on fleshing out Library as Studio, a new service model for libraries based on the principles of learning, creating, and sharing. Together, we work with her team to reimagine and harmonize physical space, staff roles, and service offerings to create better community outcomes. Instead of layering on new services to the traditional library model, we approached it from the ground up, informing the redesign of their branches and new patterns for how customers and staff co-create value.

Many libraries are making this shift, and it’s fascinating to watch the transformation. While libraries employ many people with MLS degrees (needed more than ever as it gets increasingly difficult to identify reputable sources for information), staff members are being hired from more diverse backgrounds to meet community needs. These new roles include social workers, artists, public health workers, innovation experts, and many more. This trend will only continue, requiring more innovations in service models and how libraries dedicate physical space.

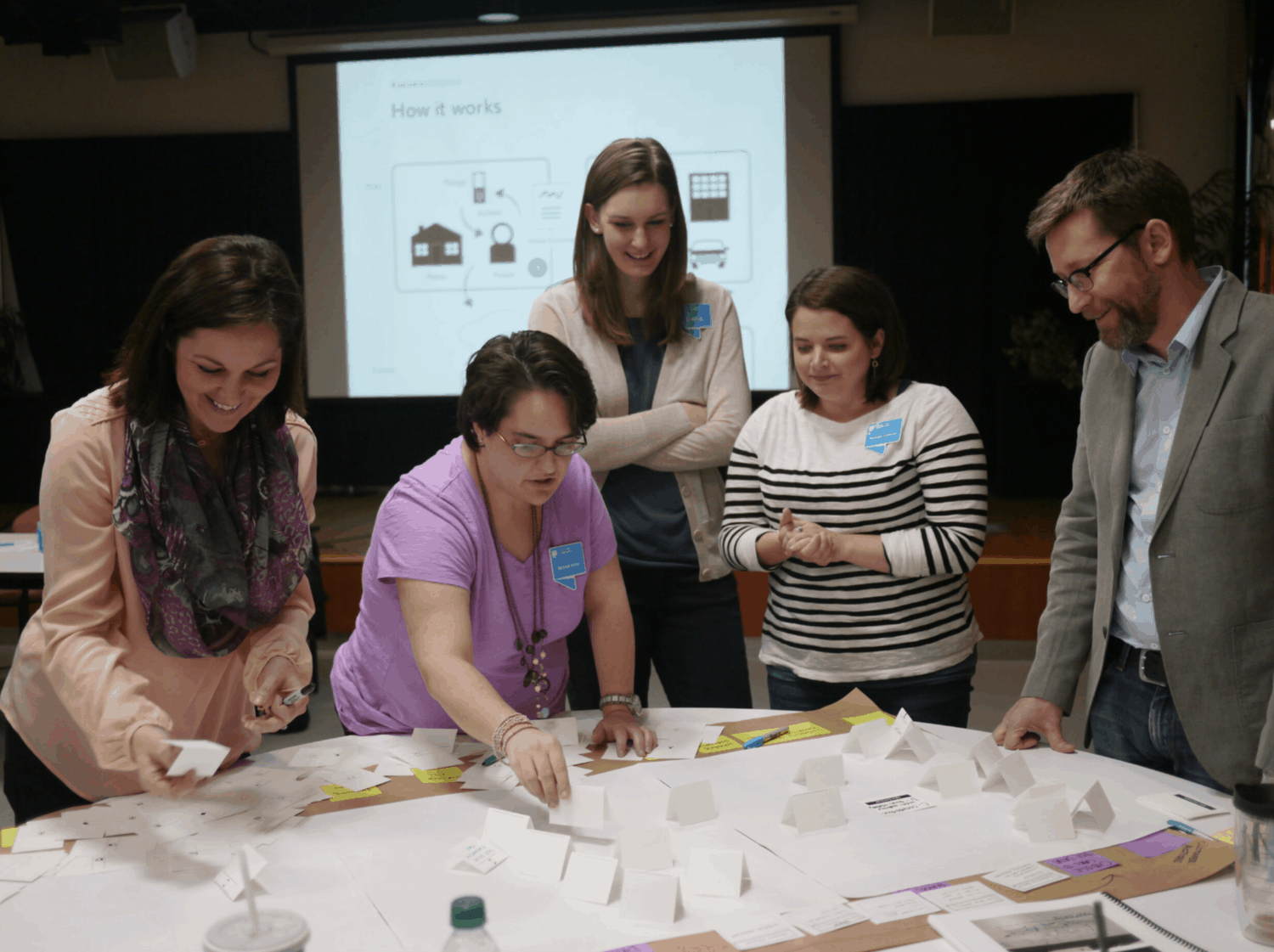

As in other domains, progressive library leaders understand they must start to rethink how staff approaches their work individually and collectively. Design thinking has become quite the hot topic in Library Land over the last decade, and now libraries are discovering service design and its unique approaches to designing holistically front stage and backstage. My team and I have had a great time teaching librarians at staff events, conferences, and strategy engagements. Techniques such as directed storytelling, experience mapping, service blueprinting, service storming, and experience principles have helped the teams we’ve worked with to define new value propositions, reimagine what customers experience, and better equip their workforce to deliver new and improved services.

Most libraries have meeting spaces for the community to gather. In most cases, they provide a room, security, and help if needed. But that’s where the service ends. But should it?

A couple of years ago, I partnered with Richland Library once again to design an event — Do Good Columbia. Inspired by the service design jam format, the library facilitated a two-day community problem-solving workshop using service design techniques to develop creative solutions to increase access to, usage, and enjoyment of the downtown region’s rivers. My role was to design the approach and tools participants would use and coach the library staff to lead small design teams during the event. It was a huge success, with two teams getting funding to implement their concepts. And, they made it real!

What’s powerful about this approach is a public library not just hosting or convening, but guiding community members through a process to understand community needs, align on desirable and viable solutions, and to take action. This is a service every community needs, and libraries have the right people, facilities, and public trust to provide it.

All of these changes become easier and more impactful once a library answers a critical question: “What does the library want its community to become?” This is inspired, of course, by Michael Schrage’s concept that “the better we know and understand who customers want to become, the better we can invest and develop the innovations necessary to get them there.”) This is a North Star that clarifies the outcomes the Public Library should work towards overtime.

When teaching library staff this concept, I explain that uncovering what the community wants to become is all about learning stories and telling new ones. One can’t uncover those stories in surveys or transactional data. Staff must go out and talk to the community and learn about the narratives unfolding in the community. These stories include where people have come from and where they are hoping to go. They reveal barriers to overcome. They inform which outcomes a library can rally around to make a reality.

These insights collectively shine a light on opportunities for the library to co-create new and better stories in their communities. To be an instrument of change. To provide a place for every citizen to reach their full potential. To celebrate who one is and what one can become.